Communication of Adverse Childhood Experiences

Our current featured article in ANS is titled “A Conceptual Model to Guide Patient-to-Provider

Communication of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Primary Care: The PPC-ACE Model” by Kimberly A. Strauch, PhD, MSN, ANP-BC. This article is available for free download and we invite you to share your comments and questions here for discussion! Dr. Strauch shared this background about her work:

This paper evolved out of praxis as a primary care nurse practitioner (NP) and nurse educator and culminated in my research as a doctoral student. Early on in my NP career I was faced with the stark realization that my nursing education and training did not prepare me to identify and address the significant bio-psycho-social issues stemming from adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) that deeply affected adults under my care. Armed with the knowledge that significant research questions emerge from clinical practice, I had many questions that needed answers and I wanted to have an impact on the health and wellbeing of the people under my care that went beyond the exam room.

As a doctoral student, I was interested in understanding how primary care NPs communicate with adults about ACE exposure, including their perceptions, experiences, and use of the electronic health record as a tool for such communication. Communicating with adults about childhood adversity is not an innate clinical skill nor is it a routine assessment element. NPs may be aware of the significance that ACE exposure has on adult health and wellbeing; however, they may not be prepared to identify, solicit, interpret, and subsequently act on that information. Presently, the concept of “trauma informed care” (TIC) has come to represent the conceptualization and delivery of ACE-related communication in a variety of healthcare settings, including primary care. This framework can be applied by clinicians to gain a better understanding of childhood trauma among adults and to establish a context of care; however, its abstract nature has made it challenging to operationalize and implement in primary care. As a result, the development of a more specific, middle range conceptual model to further operationalize and study these concepts was needed to better understand factors that influence this phenomenon. Doing so created an actionable opportunity to more richly describe critical elements that may be missing from this process.

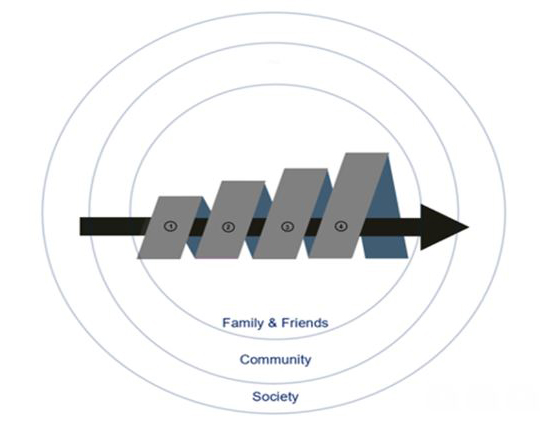

As a result, the PPC-ACE Model is a product of the synthesis and reformulation of core concepts and constructs foundational to Carrington’s (2012) Effective Nurse-to-Nurse Communication Framework (ENNCF) and Bandura’s (2004) Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). Foundational research focused on patient-to-provider communication of ACEs in the context of the primary care setting has clarified 1) how the concepts “communication” and “childhood adversity” are defined in the literature and applied to patient-to-provider communication of childhood adversity; 2) what is currently known about this phenomenon; 3) how the application of the PPC-ACE Model was used to explore the experiences and perceptions of NPs who communicate with adults about ACEs during routine primary care visits; and 4) how the conceptual model was revised based on the outcomes of the aforementioned exploratory study.

Outcomes of preliminary research using this model have informed future research focused on advanced practice nursing education and practice. Outcomes also present opportunities to shape health policy and to continue to test and refine the PPC-ACE Model. My hope is that others interested in studying this phenomenon will find this model useful in exploring and/or engaging in ACE-related communication among adults in the primary care setting, which can lead to improved mental and physical health outcomes among adults with ACE exposure.

I would like to publicly thank Dr. Pamela Reed and Dr. Jane Carrington for their expertise, encouragement, and mentorship as this conceptual model came together both during and after my time as a doctoral student.

References

Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav, 31(2), 143-164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660

Carrington, J. M. (2012). Development of a conceptual framework to guide a program of research exploring nurse-to-nurse communication. Comput Inform Nurs, 30(6), 293-299. https://doi.org/10.1097/NXN.0b013e31824af809